Globally, the construction industry is poised to service a predominantly urban population that will reach 9 billion by 2050.

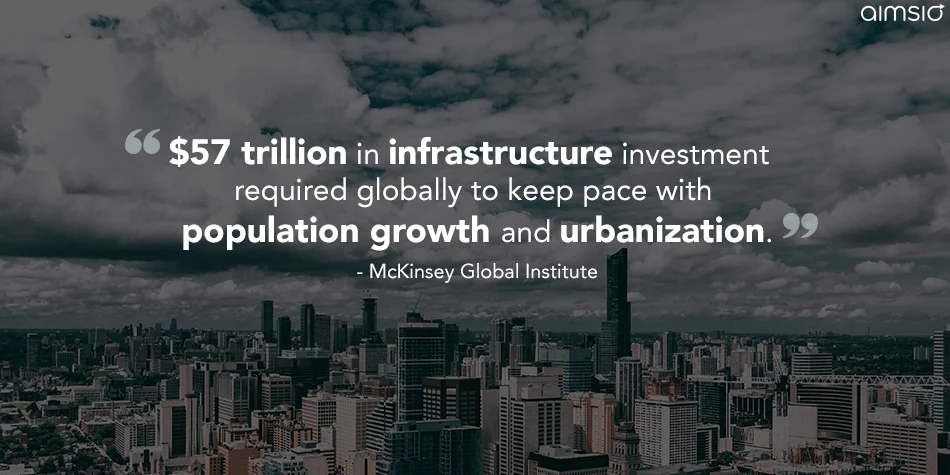

Keeping pace with growth and urbanization on this scale means significant increases in outputs are required from the heavy civil construction industry. Capital project and infrastructure spending is forecast to top $9 trillion globally in the next seven years according to Price Waterhouse Coopers and The McKinsey Global Institute puts that number at $57 trillion in the next twelve years. Specifically in North America, demand for civil infrastructure is increasing while government capital spending has declined in both Canada and the United States. While this disparity may be concerning for tax-paying citizens, it creates a unique opportunity for the industry. To compensate, governments have increased their reliance on initiatives known as Public Private Partnerships (PPPs): private firms provide upfront project investment in exchange for future profit sharing.

This should all add up to great news for the industry, but unfortunately, individual firms may not be ready to respond to the increased demand that growth and urbanization present. Poor metrics in three critical indicators suggest that the industry is underperforming to an alarming degree.

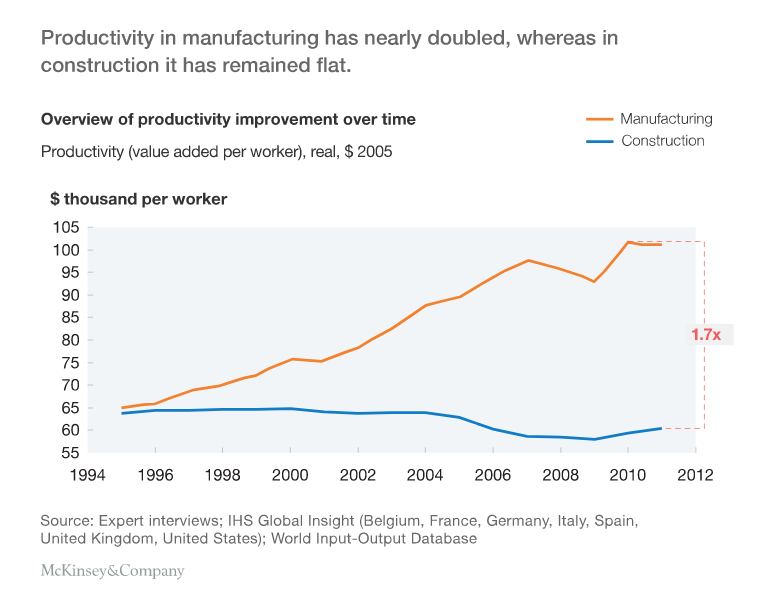

1- Productivity

In terms of value added for every hour worked, labour productivity in the global economy has been steadily increasing since the industrial revolution. Everywhere, that is, except the the construction industry where it has remained stagnant or actually declined in some markets since the 1990’s (see graph). Globally across all industries, the average worker contributes $37 of value to a project every hour. In the construction industry, however, the value added per worker is 32 percent less at just $25 per hour. In 2015, this added up to $1.6 trillion in lost productivity.

The Economist has identified two broad construction industry trends that contribute to productivity issues. First, in order to better withstand economic down-turns, the industry has become less “capital-intensive”. Workers are actually replacing machinery because, the harsh reality is, in the face of a slow-down, workers can be laid off. Equipment payments come due every month and for firms that have endured lean economic times, any way to avoid capital drains can mean long term viability. The second predicament is the industry’s ability to resist the “invisible hand” of economic principle. Efficiency should result in an advantage, as it does in other industries, squashing smaller firms and creating mega-corporations. However, it is extremely difficult to reap the benefits of scale in construction. Codes and regulations differ between regions and design differs for each project, making customization necessary, which negates the usual size advantages. This environment creates a justification trap: competition is fierce, margins are slim so reinvestment is unlikely. This unwillingness to invest has left the construction industry behind the times. Ben van Berkel, a Dutch architect, compares the construction industry to stalling in the “walkman phase”, while other industries take advantage of cutting-edge digital technology.

2 – Project Performance

An industry white paper by The Construction Users Roundtable found that 30 percent of construction costs are “wasted in the field due to coordination errors, wasted materials, labour inefficiencies and other problems with the current construction practices”. Thirty percent is certainly troubling – how does this happen? The answer may lie in the adage “what gets measured, gets managed”. Digital real-time measurement is not common practice in the industry and the impact is evident in the data: a 2015 KPMG Global survey found that in the previous three years, only 31 percent of projects came within ten percent of budget, and only 25 percent came within ten percent of the original deadline. Large projects in various construction classes (mining, infrastructure and oil and gas) typically take 20 percent longer and are up to 80 percent over budget according to McKinsey & Company.

In order to effectively manage what is measured, receiving data from site must be fast and accurate. Unfortunately, McKinsey Global notes that a lack of digitization means “information sharing is delayed and may not be universal”. Exactly what gets managed can also improve project performance. While success may mean different things to different managers on different projects, Inc. Magazine states that the right criteria is most effective when it’s chosen before a project starts. Depending on which stakeholders are considered, project performance can track client satisfaction, risk management measures, health and safety goals, and environmental impact targets.

3 – Profitability

According to Bloomberg, highway, street and bridge construction was one of the hardest hit industries after the 2008 recession. Profit margins fell ten percent, getting as low as 0.83 percent in 2010. Recovery has been slow, with recent average net profit margins in the heavy and civil engineering construction industry climbing to around four percent in 2013. This lack of growth is a sharp contrast to other construction sectors. Sageworks analyst Jenna Weaver notes that “the construction industry as a whole has kind of rebounded, and their profit margins have come back closer to pre-recession levels, where the highway and bridge construction industry has not seen that rebound.” Increasing material costs have not been found to be a contributing factor to the narrow margin, according Weaver. She does, however, suggest that with road construction, in particular, profitability requires careful management of subcontractors.

So why is the construction industry so behind?

Contributing factors:

Reluctance to go digital

McKinsey Global Institute found construction to be one of the least digitized industries. Besides the sector’s sluggishness in adopting process and technological innovations, it has not seized the opportunity to fix the basics. McKinsey notes that supply chain practices are “unsophisticated”, performance management is “inadequate” and project planning (often still done on paper) is “uncoordinated” between the office and the field. Research and development spending in the industry for technological improvements is around one percent of revenues – far below 3.5 to 4.5 percent spent in the auto and aerospace sectors.

Skilled Labour Shortages

With Baby Boomer retirement in full swing, the shortage of skilled workers experienced in the industry isn’t expected to improve anytime soon. Robert Leeds, a business development consultant at SAP, has identified a risk multiplier associated with the changing construction labour force: “the combination of increasing project complexity and decreasing experience…increas[es] the risk of deliverable delays, quality construction problems, and employee safety concerns”. It seems concerns regarding safety could certainly have merit. Construction worker fatalities and fatal injuries actually increased between 2014 and 2015 in the U.S., the only sector within the top-four most dangerous industries that failed to decrease fatal incidents during that period. For labourers, a critical entry level position, fatalities rose in 17 percent in 2015 to a rate of 15.6 deaths per 100,000 full time employees. Enticing the next generation of the workforce into the industry will be difficult, to say the least, if the current safety culture continues.

What can be done?

In a world where systems and technologies are constantly becoming obsolete, the heavy civil construction industry finds itself in the fortuitous position of being needed more than ever. One way or another, the infrastructure required to meet the demand of population growth and urbanization will be built, even conceivably at a bleak 0.83% margin. Firms that are able to improve performance and productivity stand to break the profit slump the industry is mired in. Disruption in the industry is not likely to be achieved by squeezing efficiencies from existing processes – the essential shift towards digital integration is long overdue. The shift will require changes to the industry mindset regarding reinvestment, but the potential to increase profit margins creates compelling incentive. Money spent improving coordination, managing assets, and retaining skilled workers could mean sustainable operations for the firms willing to reinvest. In order to truly capitalize with digital innovation, it is imperative that firms choose an all-in-one management system. By keeping all the new data on one platform, the simplicity and efficiency of increasing productivity, performance and profit will have stakeholders wondering why they didn’t digitize sooner.